15 years one-stop China custom CNC machining parts factory

0 |

Published by VMT at Dec 17 2025 | Reading Time:About 2 minutes

0 |

Published by VMT at Dec 17 2025 | Reading Time:About 2 minutes

You may assume that all metals rust the same way, but that assumption can lead to costly material mistakes in real-world applications. When you’re choosing materials for CNC machined parts, misunderstanding does lead rust or how lead corrosion behavior works can result in premature failure, contamination risks, or unnecessary protective treatments. The reality is that lead does not rust like iron, but it does corrode under specific conditions—and knowing the difference helps you make safer, more cost-effective machining decisions.

Lead does not rust because rust is specific to iron. However, lead does corrode and oxidize when exposed to air, moisture, acids, or sulfur compounds. This lead oxidation process forms a thin protective layer that slows further damage, giving lead relatively high lead corrosion resistance compared to many other metals.

Now that you know can lead rust is the wrong question, the real issue becomes how lead reacts in different environments and what that means for performance, safety, and durability. To fully understand does lead corrode and how its surface changes over time, you need to look at what lead corrosion actually looks like, how it forms, and how it differs from true rusting in other metals.

Lead does not rust, but it does corrode through a slow lead oxidation process when exposed to oxygen, moisture, or reactive chemicals. Unlike iron rusting, lead corrosion forms stable compounds that often protect the underlying metal, which is why lead is known for its strong lead corrosion resistance in many industrial uses, including certain CNC machined parts.

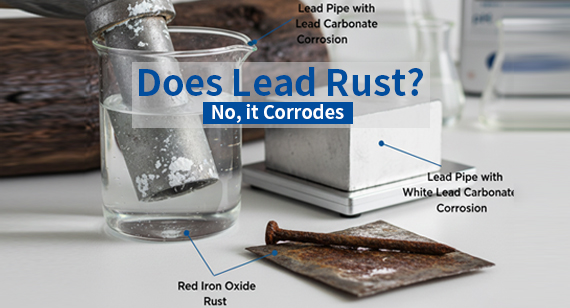

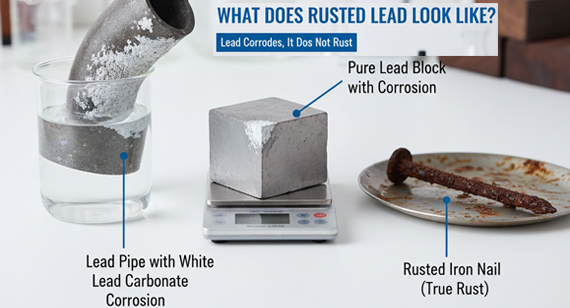

When you hear “rusted lead,” you’re actually seeing lead corrosion, not true rust. Visually, corroded lead looks dull, chalky, or powdery rather than flaky red-brown like iron rust. These surface changes come from the lead oxidation process and reactions with oxygen, moisture, acids, and pollutants. Understanding these appearances helps you correctly judge material condition before machining or reuse in CNC machined parts.

| Corrosion Cause | Description | Reaction Products | Effects |

| Reaction with Oxygen | Surface turns dull gray or whitish over time | Lead oxide (PbO) | Forms a thin protective layer that slows further corrosion |

| Corrosion in Acidic Environments | Surface becomes uneven, soft, or pitted | Lead salts (e.g., lead acetate) | Accelerates material loss and weakens structural integrity |

| Sulfur Reactions | Dark gray or black staining on the surface | Lead sulfide (PbS) | Causes discoloration and reduces surface quality |

| Formation of Carbonate Layers | White, chalky crust forms | Lead carbonate (PbCO₃) | Often protective but visually indicates long-term exposure |

| Humid Environments | Powdery white or gray buildup | Oxides and carbonates | Slow corrosion but increased surface roughness |

| General Visual Signs of Lead Corrosion | Dull, matte, non-shiny appearance | Mixed corrosion compounds | Signals oxidation rather than rusting |

| Texture Changes | Chalky, powdery, or slightly rough | Oxides, sulfides, carbonates | Can affect machining accuracy |

| Surface Patterns | Irregular patches or layered films | Multiple reaction products | Indicates uneven environmental exposure |

Note: These corrosion products explain why does lead rust is a misleading question—lead corrodes differently and more subtly.

Tip: Before sending corroded lead parts for machining, light surface cleaning can reduce tool wear and prevent dimensional errors.

When you talk about lead rusting, you’re actually describing different forms of lead corrosion behavior caused by environmental exposure. Lead does not rust like iron, but it does oxidize and corrode when specific chemical triggers are present. Understanding these causes helps you predict surface changes, control degradation, and avoid unnecessary costs when designing or machining lead-based CNC machined parts.

When lead is exposed to air, it slowly reacts with oxygen through a natural lead oxidation process. This reaction forms a thin gray or white oxide layer that adheres tightly to the surface. Unlike iron rust, this oxide layer often protects the underlying metal and limits further corrosion.

In moist air containing carbon dioxide, lead forms lead carbonate on its surface. This is why lead often develops a chalky white appearance in humid environments. The reaction is slow but persistent, especially when humidity remains high over long periods.

Sulfur-containing gases and liquids react aggressively with lead, producing dark lead sulfide layers. These reactions commonly occur in industrial or polluted environments and cause noticeable black discoloration on lead surfaces.

Chloride ions, commonly found in saltwater or industrial chemicals, can disrupt lead’s protective oxide layer. This leads to localized corrosion, pitting, and accelerated material loss, especially in marine or chemical-processing environments.

Acids react strongly with lead, forming soluble lead salts that remove material from the surface. This is one of the most damaging environments for lead and can significantly reduce its service life if left unprotected.

You’ll often see lead corrosion and lead rusting used interchangeably, but they are not the same. In fact, true rusting does not occur in lead at all. Understanding this distinction helps you correctly evaluate surface damage, predict service life, and avoid incorrect assumptions when selecting materials for CNC machined parts or industrial applications.

Tip: Using the wrong term can lead to incorrect corrosion control methods and unnecessary surface treatments.

Lead corrosion is a chemical reaction between lead and its environment, such as oxygen, moisture, acids, or sulfur compounds. During this lead oxidation process, lead forms stable compounds like oxides, carbonates, or sulfides. These layers often adhere tightly to the surface and can slow further degradation, giving lead relatively high lead corrosion resistance in many environments.

Lead rusting is a misconception. Rust specifically refers to iron oxides formed when iron reacts with oxygen and water. Since lead contains no iron, lead cannot rust. When people ask does lead rust, they are usually describing surface corrosion or oxidation, not true rust formation.

Different metals react with their environments in very different ways. When you compare lead with iron, copper, and aluminum, you quickly see why does lead rust is a misleading question. Each metal follows a unique corrosion mechanism, produces different compounds, and shows distinct visual signs. Understanding these differences helps you select the right material and surface strategy for CNC machined parts and long-term industrial use.

Rusting and Corrosion: Different Reactions of Metals

Rusting is a specific corrosion process that only applies to iron and iron-based alloys. Other metals, including lead, copper, and aluminum, corrode through oxidation or chemical reactions that often form protective surface layers. These differences directly affect durability, machinability, and lifecycle cost in CNC machining services.

| Metal | Corrosion Process | Visual Appearance | Types of Chemical Compounds Produced |

| Iron | Reacts with oxygen and water, causing continuous rusting | Reddish-brown, flaky, spreading rust | Iron oxides (Fe₂O₃, Fe₃O₄) |

| Lead | Slow oxidation and chemical reactions with air, moisture, and pollutants | Dull gray, white, or black surface films | Lead oxides, carbonates, sulfides |

| Copper | Oxidation followed by reaction with moisture and CO₂ | Brown tarnish turning green over time | Copper oxides, copper carbonate (patina) |

| Aluminum | Rapid surface oxidation forming a stable barrier | Thin, invisible or dull gray layer | Aluminum oxide (Al₂O₃) |

Note: This comparison clearly shows why can lead rust is incorrect—lead follows a corrosion path, not a rusting one.

Tip: For corrosion-sensitive applications, selecting metals with self-protective oxide layers can reduce coating and maintenance costs.

In water treatment systems, lead corrosion behavior is a critical concern. Although lead does not rust like iron, it can still corrode when exposed to water, especially if the water is acidic, contains sulfates, or has high chlorine content. Understanding how lead reacts in these environments helps you implement effective corrosion control strategies, protecting pipes, fittings, and CNC machined parts from premature damage.

Controlling lead corrosion in water systems starts with monitoring water chemistry. Adjusting pH levels, reducing dissolved oxygen, and limiting contaminants like sulfates and chlorides can slow the lead oxidation process. Proper system design also minimizes stagnant zones where corrosion is accelerated.

Applying protective coatings to lead surfaces is an effective way to prevent corrosion in water treatment applications. Common options include epoxy liners, specialized paints, or phosphate treatments. These coatings act as a barrier between lead and corrosive agents, maintaining surface integrity and prolonging part life.

Devices such as sacrificial anodes or cathodic protection systems can reduce lead corrosion in water pipelines. These systems work by redirecting corrosive reactions away from the lead, maintaining high lead corrosion resistance and protecting critical CNC machined parts in water-handling systems.

Routine monitoring and maintenance are essential for managing lead corrosion. Inspecting for surface deposits, discoloration, or pitting, and cleaning or replacing affected components helps maintain system efficiency and safety. For CNC machined parts, proper maintenance prevents dimensional issues and ensures continued precision.

Lead does not rust like iron, but it does corrode through oxidation and chemical reactions with oxygen, moisture, acids, sulfates, and other environmental factors. Its corrosion products—such as oxides, carbonates, and sulfides—often form protective layers, giving lead strong corrosion resistance compared to many other metals. Understanding the lead oxidation process, recognizing visual signs of corrosion, and controlling environmental exposure are crucial for maintaining the durability of lead components, including CNC machined parts. By implementing proper corrosion control, protective coatings, and regular maintenance, you can extend the service life of lead materials, ensure safety, and reduce long-term costs in industrial and water treatment applications.

1. Does lead rust in water?

No, lead does not rust in water. Rust is specific to iron, but lead can corrode or oxidize, forming a protective layer of oxides, carbonates, or sulfides over time.

2. Does lead rust in saltwater?

Lead still does not rust in saltwater. However, saltwater can accelerate lead corrosion behavior, especially by pitting or surface discoloration, so protective measures are recommended for exposed components.

3. Do lead pipes rust?

Lead pipes do not rust. They may develop a chalky, gray, or whitish corrosion layer, which is a result of the lead oxidation process, not rust.

4. Does lead tarnish?

Yes, lead can tarnish. Tarnishing occurs when lead reacts with sulfur, oxygen, or carbon dioxide, forming sulfides, oxides, or carbonates on the surface. This is part of normal lead corrosion behavior.

5. How fast does lead rust?

Lead does not rust, so there is no rusting rate. Its corrosion rate is generally slow, especially in neutral or dry environments, which gives it high lead corrosion resistance.

6. Does lead rust in air?

Lead does not rust in air. It slowly oxidizes, forming a dull gray or whitish surface layer that protects the underlying metal from further corrosion.

7. Does lead form rust or patina?

Lead does not form rust. It can develop a patina or thin corrosion layer, such as lead oxide, carbonate, or sulfide, depending on environmental conditions.

8. Which metal has strong rust resistance?

Metals like aluminum, copper, and lead have strong resistance to rust because they form protective oxide layers. Iron and steel, in contrast, rust easily.

9. Which metal is the hardest to rust?

Metals such as tantalum, platinum, gold, and lead are highly resistant to rust due to their low reactivity and stable surface compounds.